Testo di Cecilia Blanco e Lorenzo Sacchi

ITA

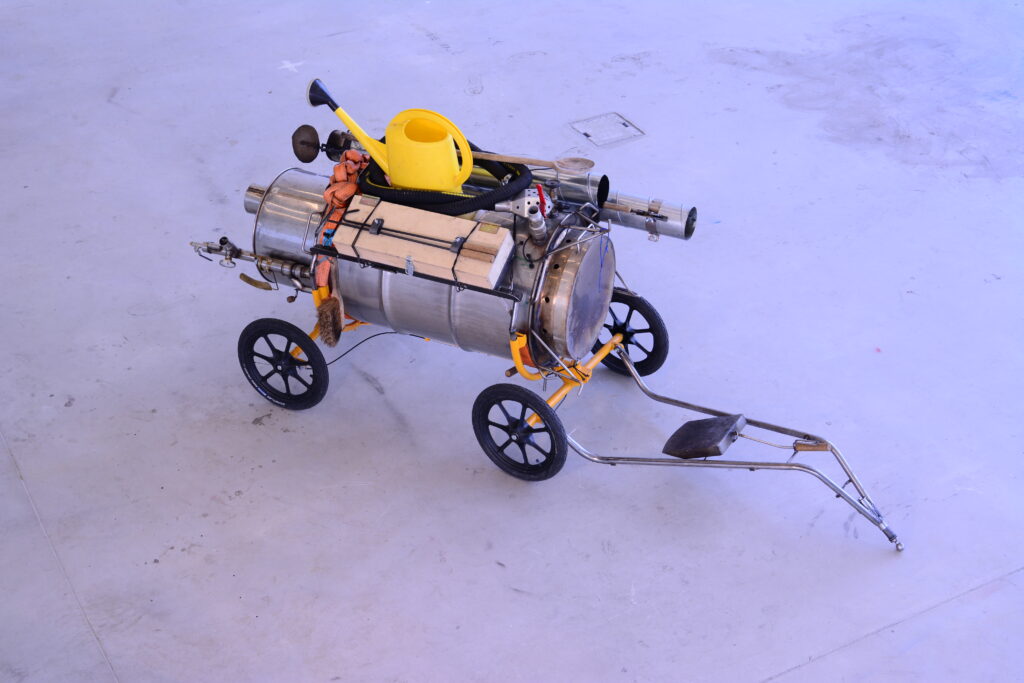

Brunnen gehn o “andare alla fontana” è l’appello del collettivo di artisti svizzeri Hotel Regina a colonizzare temporaneamente le acque, riscaldarle e rendere le fontane pubbliche in inverno uno spazio abitabile, un luogo di incontro e convivialità. Con una caldaia a legna autocostruita, una pompa azionata meccanicamente dai pedali di una bicicletta, uno spogliatoio mobile e un pentolone di tè caldo per i bagnanti, HR crea le condizioni per un’esperienza temporanea di abitare urbano. Inaugura una nuova ritualità che “occupa” la tradizione e la reinventa per territorializzarla. Inscrive questa pratica performativa immaginando una genealogia che va dalla funzione sociale delle fontane quando non c’era l’acqua corrente, attraverso la diffusione del bagno nelle terme, a l’abitudine consolidata di fare il bagno nelle fontane in estate a Basilea, fino alla tradizione del lavoro manuale in Svizzera. Progettando e realizzando a mano i vari manufatti e oggetti per l’azione, HR costruisce un’estetica e inventa una tradizione della pratica di scaldare le fontane, creando un immaginario (anche) “retroattivo” nella relazione comunità-corpo-spazio. Brunnen gehn ci permette di riflettere sul potere dirompenti dei corpi che negoziano lo spazio pubblico e lo democratizzano con quella partecipazione attiva, effimera e sperimentale.

La prima immagine che mi è venuta in mente quando ho visto questo progetto di trasformazione delle fontane pubbliche in luoghi di balneazione è stata “le gambe nella fontana”1, una foto simbolo della nascita del Peronismo, il più importante movimento politico del XX secolo in Argentina. La foto ritrae alcuni lavoratori, lavoratrici e bambini con i piedi in una fontana di Plaza de Mayo; fanno parte di una folla che arriva dalla periferia di Buenos Aires e occupa una zona della città fino ad allora vietata ai settori popolari per chiedere la liberazione del loro leader, Juan Domingo Perón. L’immagine replicata, operativa e presente nell’immaginario sociale e politico argentino dopo più di 70 anni, stabilisce una tradizione. Simboleggia l’emergere visibile del popolo; è il mito fondante di una nuova identità politica. Come un rituale coreografico di inversione, “le gambe nella fontana” evocano un potere di sovversione del senso comune dell’ordine sociale, che è anche sempre un ordine spaziale.

Richiamare alla memoria “le gambe nella fontana” e collegarlo a Brunnen gehn, al di là delle loro ovvie e chiare differenze, può essere una porta d’ingresso laterale per discutere con Hotel Regina su cosa significa abitare uno spazio, ovvero occuparlo con il nostro irriducibile corpo e dargli una forma, un significato, un’organizzazione. Ci permette di indagare il rapporto tra azioni artistiche, interventi politici, esperienze fisiche ed emotive degli abitanti e relazioni di potere nello spazio. Uno spazio che, più che un topos, è un campo relazionale, normativizzato, regolamentato, ritualizzato ma anche imprevedibile, di relazioni polemiche e non pacificate tra le persone che, a loro volta, lo attivano e lo riconfigurano. Ci sono sempre interstizi in cui generare la possibilità di interagire in modo diverso con lo spazio pubblico. La loro riappropriazione è sempre un’apertura all’imprevedibile: al limite può creare la possibilità di un ribaltamento dell’ordine socio spaziale – come dimostra l’esempio delle “gambe nella fontana” – e può anche consentire il dispiegamento di altri gesti che mostrano la relazione riflessiva tra corpo e spazio – come nel caso di Brunnen gehn. I nostri gesti ci parlano della nostra relazione con noi stessi e con lo spazio: come il corpo abita nello/con lo spazio, come lo spazio abita il corpo, cosa dicono i nostri gesti per capire queste relazioni?

Hotel Regina agisce sullo spazio attraverso le fontane balneari e trasferisce la loro agency alle persone coinvolte nella loro pratica attraverso gli strumenti da loro costruiti, che concedono ai corpi un altro modo di usare il tempo e una modalità singolare di stare. Corpi strani, vicini, plurali, complici ed empatici con l’acqua fumante della fontana. Un lavoro sensibile dei corpi. Gesti ludico-costruttivi, improduttivi, in un certo senso inutili, che mettono in discussione la prospettiva strumentale, funzionalista e produttivista dei corpi, dello spazio e degli oggetti. Alterano la politica normativizzata degli spazi pubblici attraverso micro-trasformazioni delle pratiche che vi hanno luogo.

Se “le gambe nella fontana” rivelavano anche in questo movimento politico un gesto poetico di rito iniziatico nelle acque della città proibita, Brunnen gehn – come molte delle pratiche del collettivo su cui torneremo più avanti – contribuisce a disegnare un nuovo paesaggio del visibile e del possibile in un rapporto sensuale con lo spazio. Jacques Rancière ha definito “politica dell’estetica” l’idea che l’arte possa riconfigurare il sensibile; e precisa: «Le pratiche artistiche non sono strumenti che forniscono forme di coscienza o di mobilitazione di energie a beneficio di una politica che sarebbe ad esse esterna. Ma non vanno nemmeno oltre se stesse per diventare forme di azione politica collettiva. Esse contribuiscono a disegnare un nuovo paesaggio di ciò che è visibile, di ciò che può essere detto e di ciò che è fattibile»2.

In questo senso, HR afferma: «Se dobbiamo definire il nostro approccio come politico non è perché facciamo un lavoro attivista o forniamo un servizio, non perché lavoriamo per costruire una precisa dichiarazione politica (…) Ci preoccupiamo di creare un incontro sociale, come facciamo con Brunnen gehn, perché crediamo che sia importante avere questo momento d’incontro tra diversi e non disperdersi e diventare una massa atomizzata di persone influenzabile».

Le loro pratiche sono dispositivi relazionali che generano esperienze collettive. Sono modalità d’uso e protocolli per sperimentare con lo spazio, il tempo, il corpo e la percezione. E sono, fondamentalmente, pratiche processuali che accolgono l’intenzionalità di chi partecipa e quindi suscettibili di cambiamento. «Noi costruiamo environments dove si possano fare delle cose. A differenza di prodotti che sono finiti, pensati in tutte le parti e che consentono un uso predefinito (…) Il nostro metodo è piuttosto quiet, in questo senso… Ci mettiamo in gioco chiarendo subito che non abbiamo un’idea o una conoscenza così specifica che vogliamo comunicare, ma piuttosto mettere le persone nelle nostre stesse condizioni così che possano fare esperienza loro stesse». Gli artisti di HR lavorano molto manualmente e attraverso azioni. I suoi progetti spesso iniziano con domande o idee “stravaganti”. «Nel caso di Brunnen gehn, ci siamo semplicemente chiesti ‘è possibile riscaldare una fontana per fare il bagno’ e tutto è partito da lì».

La pratica dei bagni nelle fontane è anche una riflessione sui mestieri del futuro e sulla loro tradizione. Questa ricerca, che nasce durante gli studi in post-industrial design, riguarda tanto il rapporto tra gli oggetti e il lavoro, quanto le relazioni, le istituzioni e i rituali che questo determina e con cui si evolve. Dal 2023 Brunnen gehn è quindi anche un’associazione (Verein) regolata da uno statuto e affiliata all’associazione professionale (Berufsverband) “pro fontaines chaudes”, anch’essa fondata da Hotel Regina per “mescolare quartieri, punti di vista, e strati d’acqua”, e che si occupa anche di “salvaguardare la professione del riscaldatore di fontane e di migliorare le condizioni di lavoro di chi la esercita anche attraverso la creazione di reti sovraregionali e il trasferimento di conoscenze. […] Sostiene e consiglia i riscaldatori di fontane, funge da difensore civico nelle controversie con il pubblico, l’acquedotto o la polizia e nelle questioni assicurative”. Inoltre, afferma che “quella del riscaldatore di fonti è una professione con un futuro. [Il professionista] è consapevole della necessità di una costante trasformazione ed è disposto a sottoporvisi. L’associazione pro fontaines chaudes lavora al miglioramento continuo della formazione e si adopera affinché la professione acquisti attenzione e consenso in tutta la Svizzera”. Attraverso la performance, il collettivo entra a pieno titolo nel contesto sociale ponendosi come interlocutore riconoscibile dalle istituzioni per aprire nuove strade al loro interno.

Nell’etica del lavoro svizzera, ci dice il collettivo, il lavoro manuale gode ancora di un riconoscimento e una validazione superiori rispetto al lavoro intellettuale. Così, questa pratica artistica e performativa si costruisce sullo studio di una serie di oggetti “tradizionalmente” usati dal riscaldatore di fontane e dal suo abbigliamento, intessendo con il design una nuova archeologia del rapporto tra uomo e spazio imperniata sulla relazione e sull’uso dell’acqua. La tradizione «è uno strumento per trasmettere la conoscenza, ma funziona anche come stabilizzatore perché crea continuità. Dà anche qualcosa “da fare” perché si costituisce anche di rituali. D’altra parte, proprio a causa di questa ripetizione, può essere pericolosa nel creare automatismi: la tradizione è anche fare cose senza sapere bene perché. La tradizione può anche essere molto nuova, attività e rituali che consideriamo tradizionali sono piuttosto recenti. Diciamo che vogliamo “occupare” la tradizione e creare nuovi rituali per territorializzarla, per usare un termine elegante».

Analogamente alla tradizione, la storia viene (ri)assemblata retroattivamente in funzione di una necessità del presente, come l’esercizio del potere di chi la scrive.

Così, il comune di Roma assegna una “naturale destinazione” alle fontane monumentali della città, utile all’emanazione di normative d’uso volte al mantenimento del decoro: nelle fontane storiche «è vietato pertanto: immergersi totalmente o parzialmente, […] sedersi, sdraiarsi o arrampicarsi per qualsiasi motivo, ovvero porre in essere qualsiasi altra condotta non compatibile con la loro naturale destinazione. Tutti i divieti interessano ogni parte della fontana monumentale comprese eventuali scale o scalinate»3. Laddove lo spazio pubblico si riduce a proiezione dell’autorità regolatrice, si innesca un «progressivo e sistematico processo di sottrazione fisica e simbolica dei corpi dagli spazi urbani»4. In questo modo, il significato della città slitta da “luogo di adunanza di esistenze” a spazio geometrico statico e privo di vita, e in nome della conservazione della sua matericità si legittimano norme che regolano la postura dei corpi.

Il passaggio delle fontane da oggetto funzionale e monumentale a oggetto di mantenimento del decoro è una politica dei corpi nello spazio in aperta contraddizione con la simbologia delle fontane derivata, tra l’altro, dal rapporto della comunità con l’acqua (e le dovute relazioni di potere) che ha, a sua volta, determinato la natura degli insediamenti umani.

Toccare le acque delle fontane, raccoglierle, rinfrescarsi, utilizzarle in qualsiasi modo diventa un comportamento da sanzionare. Non è concessa nessuna relazione funzionale o sensuale con l’acqua ma solo la possibilità di guardare la monumentalità mantenendo la distanza. Il primato della prospettiva in termini oculocentristi: vedere da lontano, fare dello spazio uno schema razionale e accentratore; tutto il contrario dell’abitare, che è sempre e in primis fare esperienza.

Con Confluvium, HR torna alle fontane per rompere i recinti della monumentalità, confondere le acque e dare vita a una sorta di fontana provvisoria. Durante la performance – realizzata in collaborazione con il modulo di Estetica del territorio del master in Environmnetal Humanities dell’università di Roma Tre e il collettivo di artisti ATIsuffix – un gruppo di persone cammina per il centro di Roma, raccoglie in un barile l’acqua da alcune delle sue famose fontane monumentali utilizzando ogni sorta di contenitore, a simboleggiare il carattere molteplice dell’elemento e la varietà degli usi attorno ai quali si sviluppa il design dell’oggetto, in questo caso decontestualizzato.

Sulla scalinata di Viale Glorioso, uno spazio già vissuto nelle ore notturne, dà vita ad una sorta di fontana utilizzando la pompa a pedali del progetto Brunnen gehn, per godere dell’acqua e inventare uno spazio di permanenza proprio attraverso quell’acqua “proibita” delle fontane monumentali relegata a zampilli pittorici e decorosi riservati allo sguardo. Rubare, mescolare, ibridare, usare, “confondere le acque per guadagnare spazio”5.

Il sistema di significati e usi che regola il rapporto tra una comunità e l’acqua si intreccia con i riti e con le narrazioni tradizionali e identitarie. Questa interazione ha un ruolo di primo piano nella costruzione del territorio, nella spazializzazione del senso di appartenenza e nella legittimazione di scelte politiche. Durante gli anni della seconda guerra mondiale, la Geistige Landesverteidigung (Spiritual National Defence)6 sovrappose l’identità svizzera al paesaggio alpino, eletto a simbolo, logo, o immaginario nazionale7. Hotel Regina ci racconta con un aneddoto che sono gli stessi cittadini a indicare montagne e laghi alpini come bellezza naturale del paese. E tuttavia «le montagne, questo paesaggio “naturale” associato all’identità del paese in quanto “paese rurale”, pieno di natura e autosufficiente, sono in realtà un paesaggio infrastrutturato e industrializzato, sia da un punto di vista turistico che da un punto di vista energetico».

Le dighe svizzere con bacini di volume superiore ai 10 milioni di metri cubi sono cinquanta, di cui quarantadue in ambito alpino o prealpino. Una di queste, la diga della Valle di Lei, ha una storia transfrontaliera che rivela intrecci di interessi economici, storie di sfruttamento ed equilibri politici tra Svizzera e Italia. La creazione del bacino è il risultato di un accordo bilaterale che ha comportato lo scambio di territori e lo spostamento delle linee di confine per far sì che il lago si trovasse in territorio italiano e il muro della diga in territorio svizzero. La gestione e la produzione di energia sono di pertinenza di un’azienda elvetica, che poi restituisce all’Italia una percentuale di elettricità calcolata sullo studio degli apporti idrici al lago artificiale. Tuttavia, la progettazione e la costruzione del muro coinvolsero imprese italiane e il reclutamento di manodopera poco qualificata, tanto che durante i tre anni di costruzione (1958-1960), nel solo cantiere della diga, morirono sul lavoro dodici persone8.

Il progetto Steil am Wind di Hotel Regina è una performance senza audience in cui il collettivo porta proprio sul lago di Lei, a 1930 metri sul livello del mare, una canoa modificata per andare anche a vela e a pedali. Il gruppo naviga per sei giorni «l’assurdità del lago artificiale, che non è un romantico laghetto di montagna, ma una bruta installazione tecnica,acqua in attesa di diventare elettricità». Un invito a riflettere su un modo di osservare e concepire il mondo appiattito sul paradigma tecnocratico funzionalista. L’acqua, e attraverso di essa tutto il territorio, viene ridotta a risorsa e il suo significato emerge solo in quanto elemento all’interno di una serie utilitaristica, con la conseguenza di poter essere plasmata a seconda delle necessità dello sfruttamento economico e dell’estrazione di valore. Il gesto poetico di attraversamento del lago contraddice questa visione tecnica e idealizzante entrando a contatto con la materia, con il vento, con le sponde rocciose, con la fatica di trasportare l’imbarcazione fino là. Lo spazio diventa situazionale, le distanze – geografiche, “simboliche”, affettive – vengono riconfigurate in base al nuovo uso messo in pratica e, di conseguenza, al nuovo significato che il lago assume. La fotografia e la navigazione mossa dal vento rispondono alla necessità simbolica del paesaggio attraversato mantenendo il loro carattere poetico di traccia effimera, segno momentaneo sulla superficie dell’acqua.

Se «a posteriori, possiamo dire che il lavoro ha riguardato più che altro i nostri conflitti interni attorno a questa questione dell’identità e del paesaggio», come molti lavori del gruppo, Steil am Wind nasce con un approccio scherzoso: «giocare e scherzare fanno parte del nostro processo creativo, siamo produttivi quando ci divertiamo, quindi proviamo a non prenderci troppo sul serio. In questo senso l’ironia e il gioco assumono una dimensione politica. Riconosciamo di essere un gruppo di persone privilegiate, e cerchiamo di allentare la nostra posizione di potere entrando in territori più indefiniti e insicuri per decostruire il nostro sguardo. Lo humor è anche un modo per rivelare l’assurdità del sistema in cui viviamo, delle sue regole e pratiche. In ogni caso, non siamo un collettivo di intellettuali, ma di artisti che lavorano molto manualmente e tramite azioni». Se Brunnen gehn è iniziato chiedendosi se fosse possibile scaldare le fontane per farci il bagno anche d’inverno, Steil am Wind nasce cercando di inventare un mezzo per spostarsi su tutte le superfici a partire da una canoa che avevano acquistato. Successivamente, il progetto si sviluppa attorno alla sceneggiatura di un cortometraggio, scritto da Hotel Regina, che racconta il gesto di raggiungere questo lago per scattare una sola fotografia su pellicola di medio formato. Durante i sei giorni di navigazione il collettivo scatta la fotografia e raccoglie il materiale video per il documentario omonimo.

L’ultimo lavoro di Hotel Regina di cui parliamo qui è una «camminata teatrale» intitolata I was here. Il collettivo si è ispirato all’ascesa al monte ventoso di Francesco Petrarca per organizzare una performance che stimolasse uno sguardo critico sul modo di vivere il non umano e lo spazio non urbano. Il pubblico è stato accompagnato su un monte subito fuori Zurigo, in un contesto dove potesse osservare il proprio rapporto con l’ambiente, con l’interferenza di alcuni gesti e dispositivi critici elaborati dagli artisti. «Abbiamo over-acted alcune pratiche, per esempio, nel momento in cui abbiamo messo su un “camp-fire”, tutto il materiale era già pronto, i legni erano incollati l’uno sull’altro ed erano pronti per essere accesi. Una volta sedut* attorno, abbiamo distribuito marshmallows già infilati negli stecchini. Volevamo stimolare una riflessione attorno all’idea di “instant nature”, un rapporto con il non umano – con la natura – pronto all’uso, al limite del consumo. Alla sommità del monte, dove si trova una piattaforma di osservazione attrezzata, abbiamo consegnato a ciascun* spettator* un pezzo da due franchi, ovvero il prezzo per accedervi. Ci guardiamo intorno e quello che vediamo è un paesaggio completamente antropizzato, possiamo osservare la forma e la strutturazione del territorio, la spazializzazione del nostro modo di concepirlo e di viverlo, del nostro sistema socio-economico. Ci ritroviamo a camminare in un bosco e nonostante la grande quantità di vita che ci circonda ci sentiamo soli, perché non sappiamo come stabilire un contatto». Ritorna ancora una volta quello che rintracciamo come filo conduttore di molti lavori di Hotel Regina, ovvero l’abitare, l’assegnazione di significato e valore simbolico ai luoghi, tramite l’attraversamento e la permanenza nello spazio; la problematizzazione, la presa di coscienza e la critica del “punto di vista” abituale, messo a nudo con situazioni aperte e ironiche, innescate con strumenti autocostruiti che interagiscono con la postura dei corpi in relazione al contesto, forzando le norme che regolano i rapporti tra persone, architettura, città, e non umano.

ENG

Brunnen gehn or “going to the fountain” is Swiss artist collective Hotel Regina’s call to temporarily colonize the waters, warm them up and make public fountains in winter a habitable space, a place for meeting and conviviality. With a self-built wood boiler, a pump mechanically operated by the pedals of a bicycle, a mobile changing room, and a pot of hot tea for bathers, HR creates the conditions for a temporary experience of urban habitation. It inaugurates a new rituality that “occupies” tradition and reinvents it to territorialize it. It inscribes this performative practice by imagining a genealogy from the social function of fountains when there was no running water, through the spread of bathing in thermal waters, to the established custom of bathing in fountains in summer in Basel, to the tradition of manual labor in Switzerland. By designing and handcrafting the various artifacts and objects for action, HR constructs an aesthetic and invents a tradition of the practice of warming fountains, creating an imaginary which is (also) “retroactive” in the community-body-space relationship. Brunnen gehn allows us to reflect on the disruptive power of bodies negotiating public space and democratizing it with that active, ephemeral and experimental participation.

The first image that came to my mind when I saw this project to turn public fountains into bathing places was “legs in the fountain”9, a photo symbolic of the birth of Peronismo, the most important political movement of the 20th century in Argentina. The photo depicts some workers, laborers and children with their feet in a fountain in the Plaza de Mayo; they are part of a crowd arriving from the outskirts of Buenos Aires and occupying an area of the city hitherto forbidden to popular sectors to demand the release of their leader, Juan Domingo Perón. The replicated image, operative and present in the Argentine social and political imagination after more than 70 years, establishes a tradition. It symbolizes the visible emergence of the people; it is the founding myth of a new political identity. As a choreographic ritual of inversion, “the legs in the fountain” evoke a power of subversion of the common sense of social order, which is also always a spatial order.

Calling to mind “legs in the fountain” and linking it to Brunnen gehn, beyond their obvious and clear differences, can be a side door to discuss with Hotel Regina what it means to inhabit a space, that is, to occupy it with our irreducible bodies and give it form, meaning, and organization. It allows us to investigate the relationship between artistic actions, political interventions, physical and emotional experiences of the inhabitants, and power relations in space. A space that, more than a topos, is a relational field, normalized, regulated, ritualized but also unpredictable, of contentious and unpeaceful relations between people who, in turn, activate and reconfigure it. There are always interstices in which to generate the possibility of interacting differently with public space. Their reappropriation is always an opening to the unpredictable: at the limit it can create the possibility of a reversal of the socio-spatial order – as the example of the “legs in the fountain” shows – and it can also allow the deployment of other gestures that show the reflexive relationship between body and space – as in the case of Brunnen gehn. Our gestures tell us about our relationship with ourselves and with space: how the body inhabits in/with space, how space inhabits the body, what do our gestures say to understand these relationships?

Hotel Regina acts on space through bathing fountains and transfers their agency to the people involved in their practice through the tools they construct, which grant bodies another way of using time and a singular mode of being. Strange bodies, close, plural, complicit and empathetic with the steaming water of the fountain. A sensitive work of bodies. Playful-constructive, unproductive, somewhat useless gestures that question the instrumental, functionalist and productivist perspective of bodies, space and objects. They alter the normalized politics of public spaces through micro-transformations of the practices that take place there.

If “the legs in the fountain” also revealed in this political movement a poetic gesture of initiatory rite in the waters of the forbidden city, Brunnen gehn – like many of the practices of the collective to which we will return later – contributes to drawing a new landscape of the visible and possible in a sensual relationship with space. Jacques Rancière has called the idea that art can reconfigure the sensible “politics of aesthetics”; and he points out, “Artistic practices are not tools that provide forms of consciousness or mobilization of energies for the benefit of a politics that would be external to them. But neither do they go beyond themselves to become forms of collective political action. They help draw a new landscape of what is visible, what can be said and what is feasible”10.

In this sense, HR states, “If we have to define our approach as political, it is not because we do activist work or provide a service, not because we work to construct a precise political statement (…) We are concerned with creating a social encounter, as we do with Brunnen gehn, because we believe that it is important to have this moment of encounter between different people and not to disperse and become an atomized mass of influenceable people.”

Their practices are relational devices that generate collective experiences. They are modes of use and protocols for experimenting with space, time, body and perception. And they are, fundamentally, processual practices that accommodate the intentionality of those who participate and are thus susceptible to change. “We build environments where things can be made. As opposed to products that are finished, thought out in all parts, and allow for predefined use (…) Our method is rather quiet, in that sense… We go out on a limb by making it clear right away that we don’t have such a specific idea or knowledge that we want to communicate, but rather put people in the same conditions as us so that they can experience it themselves.” HR’s artists work very manually and through actions. Their projects often begin with “quirky” questions or ideas. “In the case of Brunnen gehn, we simply wondered ‘is it possible to heat a fountain for bathing,’ and it all went from there.”

The practice of bathing in fountains is also a reflection on the crafts of the future and their tradition. This research, which originated during studies in post-industrial design, is as much about the relation between objects and work as it is about the relationships, institutions, and rituals that this relation determines and with which it evolves. Since 2023, Brunnen gehn has thus also been an association (Verein) governed by statutes and affiliated with the professional association (Berufsverband) pro fontaines chaudes, which was also founded by Hotel Regina to “mix neighborhoods, points of view, and layers of water”, and which is also concerned with “safeguarding the profession of fountain heater and improving the working conditions of those who practice it, including through the creation of supra-regional networks and knowledge transfer. […] It supports and advises fountain heaters, acts as an ombudsman in disputes with the public, waterworks or police, and in insurance matters.” It further states that “that of the source heater is a profession with a future. [The professional] is aware of the need for constant transformation and is willing to undergo it. The association pro fontaines chaudes works on the continuous improvement of training and works to ensure that the profession gains attention and acceptance throughout Switzerland.” Through performance, the collective enters fully into the social context by positioning itself as a recognizable interlocutor for institutions to break new ground within them.

In the Swiss work ethic, the collective tells us, manual labor still enjoys greater recognition and validation than intellectual labor. Thus, this art and performance practice is built on the study of a series of objects “traditionally” used by the fountain heater and his clothing, weaving with design a new archeology of the relationship between man and space hinged on the relationship and use of water. Tradition “is a tool to transmit knowledge, but it also works as a stabilizer because it creates continuity. It also gives something “to do” because it constitutes rituals.” On the other hand, precisely because of this repetition, it can be dangerous in creating automatisms: tradition is also about doing things without really knowing why. Tradition can also be very new; activities and rituals that we consider traditional are quite recent. We say we want to ‘occupy’ tradition and create new rituals to territorialize it, to use an elegant term.”

Similar to tradition, history is retroactively (re)assembled according to a necessity of the present, such as the exercise of the power of those writing it. Thus, the municipality of Rome assigns a “natural destination” to the city’s monumental fountains, which is useful for the enactment of regulations of use aimed at maintaining decorum: in the historic fountains “it is therefore forbidden: to immerse oneself totally or partially, […] to sit, lie down or climb for any reason whatsoever, or to engage in any other conduct that is not compatible with their natural destination. All prohibitions affect every part of the monumental fountain including any stairs or steps”11. Where public space is reduced to a projection of regulatory authority, it triggers a “progressive and systematic process of physical and symbolic subtraction of bodies from urban spaces”12. In this way, the meaning of the city slips from a “place of gathering existences” to a static and lifeless geometric space, and the preservation of its materiality legitimizes norms regulating the posture of bodies.

The shift of fountains from a functional and monumental object to an object of maintaining decorum is a policy of bodies in space in open contradiction to the symbology of fountains derived from, among other things, the community’s relationship with water (and the due power relations) which has, in turn, determined the nature of human settlements.

Touching fountain waters, collecting them, refreshing oneself, using them in any way becomes a behavior to be sanctioned. No functional or sensual relationship with water is allowed, only the possibility of looking at monumentality while maintaining distance. The primacy of perspective in oculocentrist terms: seeing from afar, making space a rational, centralizing pattern; the whole opposite of inhabiting, which is always and primarily experiencing.

With Confluvium, HR returns to fountains to break the fences of monumentality, muddle the waters and give life to a kind of temporary fountain. During the performance – realized in collaboration with the Esthetic of Landscape module within the Master in Environmental Humanities at the University of Roma Tre and the artist collective ATIsuffix – a group of people walk through the center of Rome, collecting water in a barrel from some of its famous monumental fountains using all sorts of containers, symbolizing the multiple character of the element and the variety of uses around which the design of the object, in this case decontextualized, is developed. On the steps of Viale Glorioso, a space already experienced in the night hours, they gives life to a kind of fountain using the pedal pump of the Brunnen gehn project, to enjoy water and invent a space of permanence precisely through that “forbidden” water of monumental fountains relegated to pictorial and decorous gushes reserved for the gaze. Stealing, mixing, hybridizing, using, “confusing the waters to gain space”13.

The system of meanings and uses that governs the relationship between a community and water is intertwined with rituals and traditional and identity narratives. This interaction plays a major role in the construction of territory, the spatialization of a sense of belonging, and the legitimization of political choices. During the years of World War II, the Geistige Landesverteidigung (Spiritual National Defence)14 carried out by the government superimposed Swiss identity on the Alpine landscape, elected as a national symbol, logo, or imaginary15. Hotel Regina tells us with an anecdote that it is the citizens themselves who point to mountains and Alpine lakes as the natural beauty of the country. And yet, “the mountains, this ‘natural’ landscape associated with the country’s identity as a ‘rural country,’ full of nature and self-sufficient, is actually an infrastructured and industrialized landscape, both from a tourism and energy perspective.” There are fifty Swiss dams with reservoirs greater than 10 million cubic meters in volume, forty-two of which are in the Alpine or pre-Alpine area. One of these, the Lei Valley Dam, has a cross-border history that reveals intertwined economic interests, exploitation histories and political balances between Switzerland and Italy. The creation of the reservoir was the result of a bilateral agreement that involved exchanging territories and shifting border lines so that the lake was on Italian territory and the dam wall on the Swiss one. Energy management and production are the responsibility of a Swiss company, which then returns to Italy a percentage of electricity calculated on the study of water inputs to the reservoir. However, the design and construction of the wall was carried together with italian companies and recruiting poor italian workers, and during the three years of construction (1958-1960), twelve people died on the job at the dam site alone.16

Hotel Regina’s Steil am Wind project is a performance without an audience in which the collective takes a canoe modified to sail and pedal on Lake Lei, 1930 meters above sea level. The group navigates for six days “the absurdity of the artificial lake, which is not a romantic mountain lake, but a brute technical installation, water waiting to become electricity”. An invitation to reflect on a way of observing and conceiving the world flattened by the technocratic functionalist paradigm. Water, and thus the whole territory, is reduced to a resource and its meaning emerges only as an element within a utilitarian series, with the consequence that it can be shaped according to the needs of economic exploitation and value extraction. The poetic gesture of crossing the lake contradicts this technical and idealizing vision by coming into contact with the material, with the wind, with the rocky shores, with the toil of transporting the boat there. Space becomes situational, distances – geographical, “symbolic,” affective – are reconfigured according to the new use put to it and, consequently, the new meaning the lake takes on. Photography and navigation moved by the wind respond to the symbolic necessity of the crossed landscape while maintaining their poetic character of ephemeral trace, momentary sign on the surface of the water.

While “in retrospect, we can say that the work has been more about our internal conflicts around this question of identity and landscape,” like many of the group’s works, Steil am Wind was born with a playful approach: “playing and joking are part of our creative process, we are productive when we’re having fun, so we try not to take ourselves too seriously. In this sense, irony and playfulness take on a political dimension. We recognize that we are a privileged group of people, and we try to loosen our position of power by entering into more undefined and insecure territories to deconstruct our outlook. Humor is also a way to reveal the absurdity of the system we live in, its rules and practices. In any case, we are not a collective of intellectuals, but of artists who work very manually and through actions”. If Brunnen gehn began by wondering if it would be possible to heat fountains to bathe in them even in winter, Steil am Wind was born by trying to invent a means of moving over all kinds of surfaces starting from a canoe they had purchased. Subsequently, the project developed around the script of a short film, written by Hotel Regina, about the act of reaching this lake to take a single photograph on medium format film. During the six days of sailing, the collective takes the photograph and collects the video material for the documentary of the same name.

One of the latest works by Hotel Regina discussed here is a “theatrical walk” entitled I was here. The collective was inspired by Francesco Petrarca’s Ascesa al Monte Ventoso to organize a performance that would stimulate a critical look at the ways of experiencing nonhuman and nonurban space. The audience was taken to a mountain just outside Zurich, in a context where they could observe their own relationship with the environment, through the interference of some gestures and critical devices developed by the artists. “We over-acted some practices, for example, the moment we set up a camp-fire, all the material was already ready, the woods were glued on each other and were ready to be lit. Once we sat around, we handed out marshmallows already tucked into the sticks. We wanted to stimulate reflection around the idea of “instant nature,” a relationship with the nonhuman – with nature – ready to use, at the edge of consumption. At the top of the mountain, where there is an equipped observation platform, we handed each viewer a two-franc piece, which is the price to access it. We look around and what we see is a completely man-made landscape, we can observe the shape and structuring of the land, the spatialization of the way we conceive and experience it, of our socio-economic system. We find ourselves walking in a forest and despite the large amount of life around us we feel lonely because we don’t know how to make contact.” Once again we return to what we trace as a common thread in many of Hotel Regina’s works, namely inhabiting-dwelling, meaning and assigning symbolic value to places through crossing and staying in space; problematizing, becoming aware of and critiquing the habitual “point of view,” laid bare with open and ironic situations, triggered with self-made tools that interact with the posture of bodies in relation to the context, forcing the norms that regulate the relationships between people, architecture, the city, and the non-human.

- Foto del 17 di ottobre di 1945. https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:17deoctubre-enlafuente.jpg ↩︎

- Rancière, J. (2002). La división de lo sensible. Estética y Política, Salamanca: Consorcio Salamanca. È la distribuzione del sensibile, i modi di vedere, di dire, di fare, l’ordinamento di oggetti e corpi, l’assegnazione di posti e funzioni in relazione a un ordine sociale, ciò che hanno in comune arte e politica. L’arte è politica nella misura in cui, come la politica stessa, irrompe nella distribuzione del sensibile, generando nuove configurazioni dell’esperienza sensoriale (traduzione a cura di chi scrive). ↩︎

- È da sottolineare che l’articolo 8 del Regolamento della Polizia Urbana specifica che “la tradizione di lanciare monete in talune fontane del centro storico non rientra nel divieto”. Però “è vietata la raccolta delle monete da parte di soggetti non autorizzati”. ↩︎

- Annalisa Metta (2021). Corpo a Corpo, Ri-vista. Research for landscape architecture, Vol. 19 No. 2: Rethinking Public Space. The intangible design. ↩︎

- Ballata dell’acqua confusa, testo di Confluvium https://www.atisuffix.net/confluvium ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spiritual_national_defence ↩︎

- «Il turismo iniziò intorno al 1800 e allo stesso tempo il romanticismo trasformò la percezione delle Alpi da un deserto mortale abitato da fantasmi e altre creature in un gioiello naturale dove gli abitanti vivevano in modo originale e autodeterminato. In questo periodo Schiller scrisse il suo Wilhelm Tell, che in seguito divenne il primo eroe nazionale della Svizzera. In ogni caso, il moderno Stato federale della Svizzera fu fondato nel 1848 con la sua prima costituzione. Solo nel XX secolo la Svizzera si trovò ad affrontare regimi totalitari quasi ovunque. L’identità nazionale della Svizzera come Stato multiculturale acquistò quindi importanza per respingere le idee tedesche di integrare le parti della Svizzera di lingua tedesca nel cosiddetto imperium tedesco. In questo periodo le narrazioni romantiche come il Guglielmo Tell offrivano un potenziale perfetto in cui identificarsi». ↩︎

- Suggeriamo la visione del breve documentario del 1961 sulla costruzione della diga di Lei intitolato Un metro lungo cinque girato da Ermanno Olmi: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_hgZowxYig ↩︎

- Photograph from the 17th of October 1945. https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:17deoctubre-enlafuente.jpg ↩︎

- Rancière, J. (2002). La división de lo sensible. Estética y Política, Salamanca: Consorcio Salamanca. “It is the distribution of the sensible, the ways of seeing, saying, and doing, the ordering of objects and bodies, the assignment of places and functions in relation to a social order, what art and politics have in common. Art is political insofar as, like politics itself, it breaks into the distribution of the sensible, generating new configurations of sensory experience” (our translation). ↩︎

- The 8th article of the Urban Police Regulation specifies that “the tradition of throwing coins in some of the central fountains is not prohibited, but it is forbidden to collect them for unauthorized people”. ↩︎

- Annalisa Metta (2021). Corpo a Corpo, Ri-vista. Research for landscape architecture, Vol. 19 No. 2: Rethinking Public Space. The intangible design. ↩︎

- Ballata dell’acqua confusa, text accompanying Confluvium. https://www.atisuffix.net/confluvium ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spiritual_national_defence ↩︎

- «While tourism started around 1800, at the same time romanticism turned the perception of the alps from a deadly desert inhabited by ghosts and other creatures to a natural jewel where the inhabitants lived in an original and self-determined way. At this time Schiller wrote his Wilhelm Tell who later advanced to Switzerland number one national hero. Anyway, the modern nation federal state of Switzerland was founded in 1848 by its first constitution. Only in the 20th century Switzerland was facing totalitarian regimes nearly all around. So the national identity of Switzerland as a multicultural state gained importance to push back german ideas of integrating german speaking parts of Switzerland into the so called german imperium. At this time romantic narratives like Wilhelm Tell offered a perfect potential to identify with». ↩︎

- We suggest to watch the 1961 short documentary Un metro lungo cinque directed by Ermanno Olmi in 1961 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_hgZowxYig ↩︎